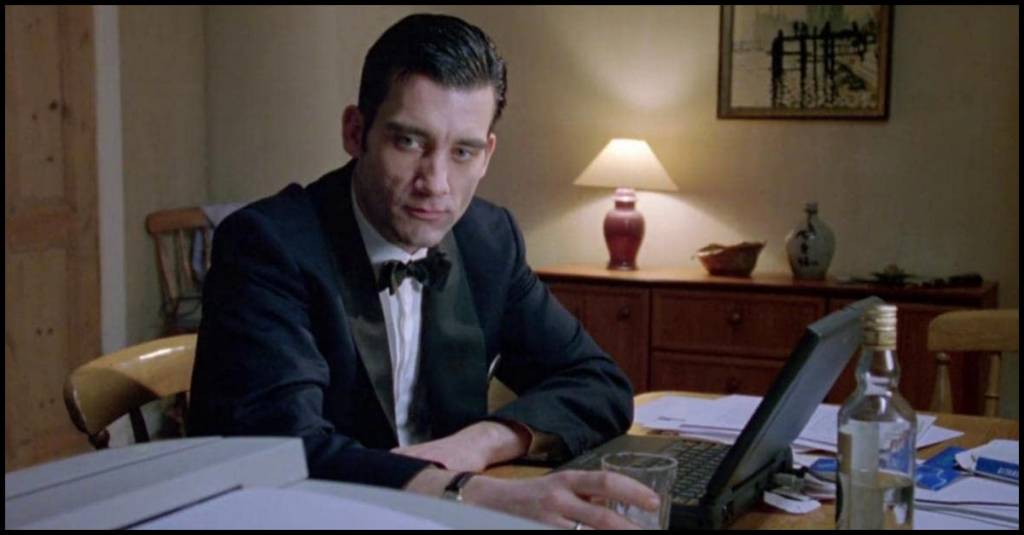

Croupier turned 25 this year, and its anniversary screening at the Laemmle Royal in Los Angeles was the perfect reminder of why this noir sleeper still slaps. A slow-burn character study wrapped in a heist plot, it introduced Clive Owen to American audiences as a force of stillness, control and coiled intensity.

Watch Clive Owen’s full Q&A below, which features insights on the film’s unlikely success, his method for capturing Jack’s interiority and the career that followed.

Directed by Mike Hodges, Croupier follows Jack Manfred, a struggling writer in London whose father pushes him into taking a job as a casino dealer. But Jack isn’t there to make tips or chase thrills. He’s an observer. Cool. Emotionally withdrawn. Built for discipline.

Jack doesn’t gamble. He studies the gamblers. He watches them implode with a detached kind of satisfaction, the way a rich dude might watch traffic from a penthouse apartment.

But when he’s drawn into a super sketchy situation with a femme fatale and the world he’s chronicling starts to bleed into his own, Jack crosses a line and pays for it.

Croupier is a movie about detachment as a survival skill. About what it means to watch instead of feel. To write instead of react. Jack is a croupier second and a writer first and that’s what fuels his need for control. His narration doesn’t just accompany the film; it is the film. The voiceover is so essential to Jack’s character that it had to be in the room, even when it wasn’t being recorded.

As Clive Owen explained in the Q&A after the screening:

“If we’d just done general card stuff and laid voiceover over it, I don’t think it would hold the same thing. It means that the voiceover is present and it’s alive.”

He didn’t treat the narration like something to be added in post-production. He learned it like dialogue, breathed it in as part of Jack’s rhythm.

“I was running the voiceover in my head all the time. It’s where Jack lives.”

That inner life, what Owen called “a character built from the inside out,” is what makes Jack so magnetic. He’s not expressive, he’s exacting. A man ruled by structure and the illusion that staying one step removed will protect you from the fallout.

Inevitably, that illusion cracks. Jack crosses a line, loses his grip and pays the price. But he doesn’t spiral.

He resets and returns to his ancient word processor. Because, in Jack’s universe, if you understand the rules, you can crawl back from almost anything.

The Laemmle Royal on Santa Monica Blvd. was the ideal setting for the screening. Built in 1924 and originally known as the Tivoli, the theater feels like a time capsule: slightly frayed and full of reverence for story and silence. It’s the kind of place where Croupier doesn’t just play; it lingers.

The film was never expected to make it. It barely got a one-week theatrical release in the UK. Even the people behind it didn’t seem to believe in it. But one person did: Mike Kaplan, a veteran publicist who saw what the film could be and championed it with old-school muscle.

“If it wasn’t for Mike championing this tiny film… my life and career would’ve been very, very different,” Owen said.

The film didn’t break box office records, but it broke through. It played for nearly a year in U.S. theaters, gaining cult status and earning Owen comparisons to James Bond (because of the tux and stoic nature of his performance, mostly). That role didn’t happen, but what came next did: Children of Men, Inside Man, The Knick, the kind of work that cemented Owen as the thinking person’s leading man.

During the Q&A, Owen spoke with the same quiet pragmatism that defines his character. He talked about Croupier as a major turning point in his career.

“Success is really about the opportunity to work with good people… That’s what Croupier did for me.”

He spoke about restraint in the performance, about how the film’s quiet tension came from resisting the urge to show too much: “You don’t have to do more to mean more.”

He also reflected on the danger of rising too fast in the film industry, when suddenly no one tells you no, and ego replaces instinct. What’s endured, he said, is the desire to choose work that sparks something real. That’s still the compass he uses to pick roles.

It’s the same one Jack Manfred lives by. For anyone wired toward clarity, structure, a sense of justice and occasional , it’s the only compass that makes sense.02

Leave a comment