The New York Times recently asked filmmakers, actors and other creatives to list their favorite films of the 21st century so far. And the result is an incredible, sprawling watchlist full of deep cuts and critical darlings. It’s the kind of thing that could keep your Letterboxd queue full for the next five years.

One of the most compelling entries came from Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk director Barry Jenkins, whose list reads like a syllabus in emotional complexity and formal boldness. His choices reflect his own sensibilities, with stories that explore identity, memory, repression, longing and the subtle ways power and history shape individuals.

Also worth noting: Moonlight appeared on multiple other people’s lists, so I think it’s likely to wind up in the Top 10 once everything is said and done. But Jenkins didn’t include his own work. Instead, he highlighted 10 films that seem to have inspired and informed him, both emotionally and stylistically.

Here’s a breakdown of his list, along with some context about the films and what they might reveal about Jenkins’ cinematic language:

1. Saint Omer – Directed by Alice Diop

Based on a real French infanticide trial, this courtroom drama resists every convention of the genre. Diop’s approach echoes Jenkins’ own trust in silence and performance.

The film centers on Rama, a novelist attending the trial of a woman accused of killing her infant daughter for research, but it’s the accused defendant who slowly takes over the emotional weight of the film. Through static, unblinking compositions and long monologues delivered with unnerving calm, Diop asks the audience to witness, rather than judge. And that ambiguity is intentional because the truth is complicated.

2. Vortex – Directed by Gaspar Noé

Best known for sensory overload, Gaspar Noé took a way different turn with Vortex, an intimate film about an elderly couple facing the slow, disorienting collapse brought on by dementia. Told entirely in split-screen, the film is more empathetic than sappy and it’s definitely not an easy watch.

Like Jenkins, Noé trusts the viewer to stay with the discomfort and find meaning in witnessing this moment in this couple’s lives.

3. Nickel Boys – Directed by RaMell Ross

In this adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s novel, two Black teens try to survive a brutal Florida reform school. Ross uses immersive POV and stillness to depict institutional violence and buried pain: two of Jenkins’ core themes.

The storytelling is unbelievably daring, and the emotion cuts clean through. This one left me in shambles and excited about the future of cinema.

4. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia – Directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan

A small convoy of men, including police officers, a prosecutor and a doctor, search the Turkish countryside for a buried body. The case is simple, but the film is more complicated than rocket science.

Most of the runtime unfolds in real time, across a long, quiet night where nothing moves quickly and no one says what they mean. The real drama happens in glances and pauses, in what is withheld rather than revealed.

5. Synecdoche, New York – Directed by Charlie Kaufman

Time collapses. A man builds a replica of his life inside a warehouse. A full-on existential spiral, and one of the most intensely emotional films about mortality. Feels like a cousin to Beale Street, if Jenkins leaned into chaos instead of grace.

6. Zodiac – Directed by David Fincher

Zodiac is, on the surface, a super detailed true-crime procedural about the infamous Zodiac Killer. But beneath all the clues and red herrings, it’s really a story about obsession and disintegration. Fincher chooses to focus on what the endless pursuit of meaning does to the people chasing it rather than cracking the actual case.

At first glance, Fincher’s precision and detached tone might seem worlds apart from Jenkins’ more intimate style. But both directors are deeply interested in the cost of pursuit and what happens when people chase clarity in a world that refuses to give it.

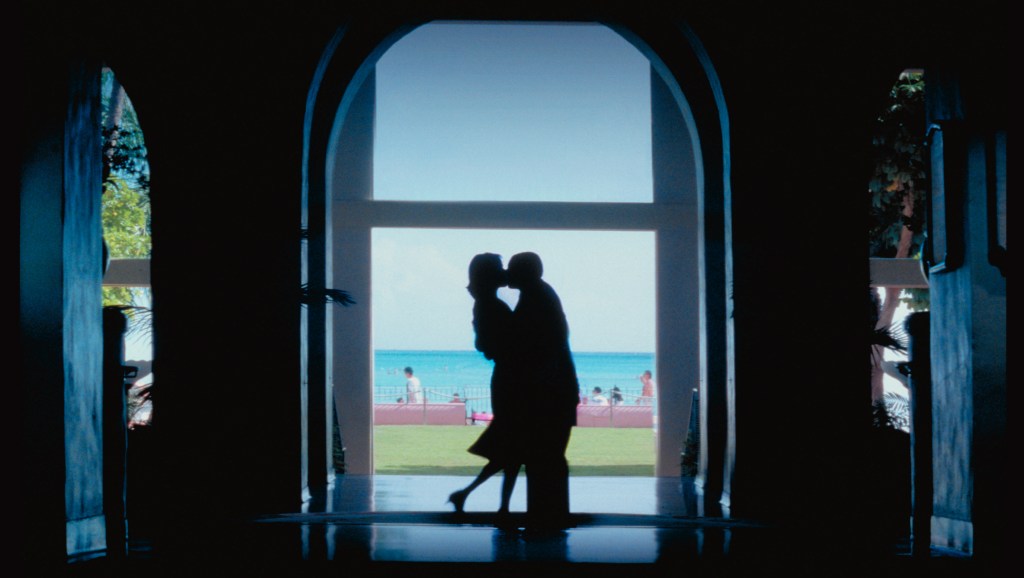

7. Punch-Drunk Love – Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

This is a love story, but one where the tenderness has to fight its way through anxiety, rage, and isolation. Paul Thomas Anderson builds a jittery, unpredictable world around a lonely man on the verge of emotional collapse. The visuals are saturated, the score swells and stumbles, and everything feels slightly off-center—until love, somehow, levels it out.

Jenkins has talked about this film as a formative influence, and it shows. From the ultra-lush visuals to the tension between chaos and intimacy, you can feel it all pulsing through Moonlight, especially in the second act. Both films take men who are fragile in different ways and give them the space to be cracked open by connection.

8. Caché – Directed by Michael Haneke

In this unsettling Haneke joint, a couple starts receiving surveillance tapes of their home. That simple premise opens up a story about guilt and the long shadows of colonial violence. Haneke keeps the camera still and distant, forcing the audience to sit in discomfort and look for meaning in the margins.

There’s no catharsis here, just a slow, steady unearthing of things long buried. Jenkins also works with buried histories, especially in Beale Street and The Underground Railroad. He shares Haneke’s interest in what characters refuse to confront, and how the past lingers whether or not we acknowledge it.

9. The Holy Girl (La Niña Santa) – Directed by Lucrecia Martel

Set in a fading hotel during a medical convention, Martel’s film focuses on a teen girl navigating the murky overlap between religious devotion, sexuality and power. Conversations blur into one another. Rooms hum with sound. Emotions are communicated through glances and half-heard dialogue. Nothing is obvious, and everything feels charged.

Martel’s style is immersive. She builds a world where what’s unsaid is louder than what’s spoken. Jenkins clearly shares that sensibility, letting tone and texture carry emotional weight instead of leaning on exposition.

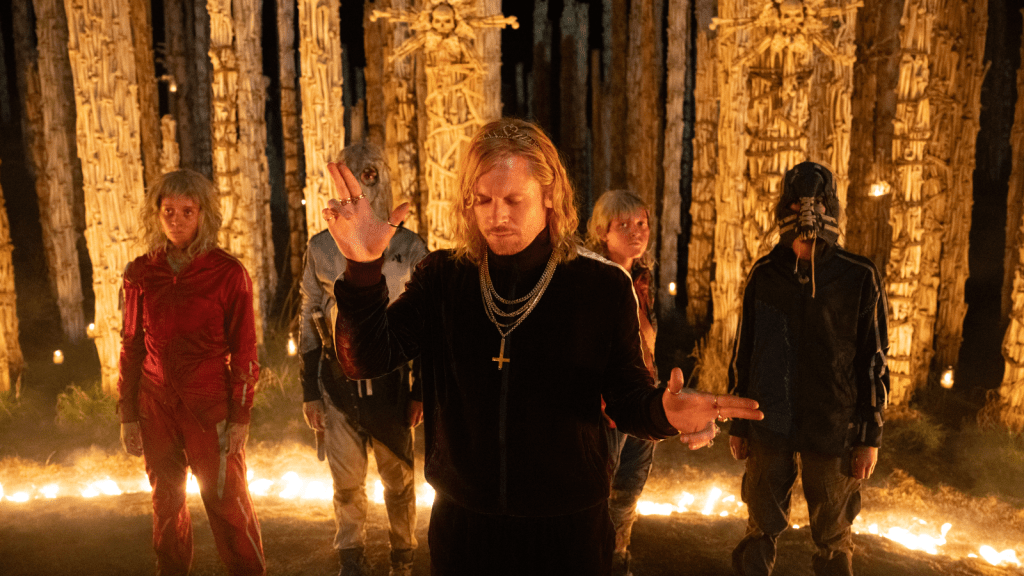

10. Elephant – Directed by Gus Van Sant

A school day unfolds in long, unbroken tracking shots, each one following a different student through hallways and quiet moments that initially seem mundane, until they aren’t. Elephant is a meditation on violence without sensationalism. There is no score, just an eerie normalcy that slowly turns to dread.

In this pivotal indie, Van Sant lets silence do the work. The film doesn’t explain or moralize. It observes. That same approach runs through Jenkins’ work, particularly in The Underground Railroad, which also treats violence as something shaped by systems and silence.

Leave a comment