Adulthood can be stressful and debilitating at times, but many of us are equipped to survive it because we endured the particular horrors of adolescence.

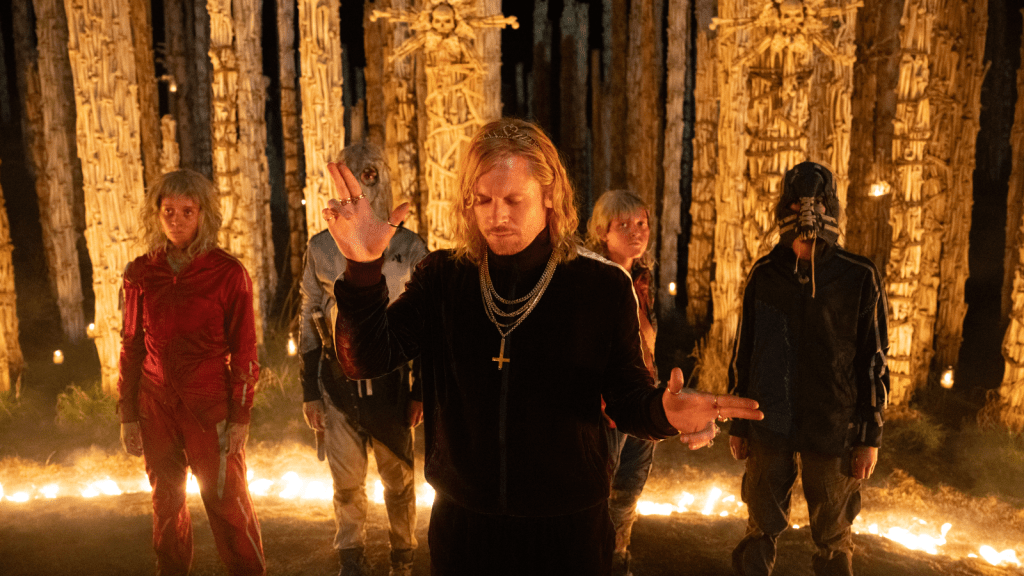

Charles Polinger’s new coming-of-age thriller, The Plague, shows how a seemingly normal summer at a water polo camp can be more traumatic than spending the night on Elm Street or locking eyes with Pennywise on a walk past a sewer drain in Derry.

Being a tween is frightening. Childhood is shrinking in your rearview mirror and the great unknown of teenhood (teenagerdom?) looms ahead. Social hierarchies are always in play in modern life, starting practically in pre-K, but around age 12, the pecking order begins to shift crazy fast.

You are perceived hard. Your body aches as your bones grow and your appetite skyrockets. Some kids grow wider before they grow taller, and others deal with hormonal fluctuations that announce themselves loudly on their faces. Everyone is watching everyone else, and no one knows the rules yet. It’s a straight-up horror show and most parents have no idea how to provide proper support, despite living through this themselves.

Like its predecessor, Lord of the Flies, The Plague is one of those movies that understands the horrors of adolescence, and it uses an anxiety-inducing score that elevates the tension in a way that I haven’t experienced since Challengers.

Set in 2003, at an all-boys summer water polo camp that looks wholesome and character-building, the film starts off innocently enough but quickly reveals itself as a study of how cruelty flourishes in spaces that appear safe on the surface.

The film follows Ben, an anxious and introverted middle schooler whose main personality trait is wanting everyone to like him, arguably one of the most dangerous traits a kid (or adult) can have.

In an early cafeteria scene—and I’m stressed just thinking about it—Ben scans the room for somewhere to sit and gravitates toward the popular table, where Jake, the camp’s unofficial perpetually smirking leader, presides over a group of knuckleheads who maintain their bond through insults and crude banter.

The first sign that Ben is in trouble happens almost immediately. He’s trying to jump into the conversation and the camera stays on Jake as he sizes Ben up, and then the bomb drops. Jake notices that Ben does not pronounce the “T” in the word “stop.”

He halts all conversations and points this out, putting Ben on the spot by asking him to say the word. Ben tries to shrug it off, but Jake is locked in and will not leave him alone until he obeys. And you’ll start to tense up in your seat as Ben caves and fails to pronounce the word, earning himself the nickname “Soppy.” To make matters worse, Ben is from Bos(t)on.

It is such an irrelevant thing to hone in on, but Jake, like all bullies, is deeply insecure and always scanning for weaknesses so his own never get exposed. Something as small as a speech tic is enough to reassert his dominance and ensure Ben won’t threaten his place at the top. Jake is the alpha bully, and Ben, ever the people-pleaser, laughs it off. Surprisingly, the group embraces him.

Maybe that acceptance comes easily because they already have a target: Eli, an eccentric kid with severe eczema who they’ve branded “the plague,” because children are nothing if not imaginative when it comes to weaponizing disgust.

We never learn whether Eli was ever part of the group or cast out from the start, but he is not the first camper to have “the plague.” Jake mentions that another kid had it the summer prior. How long has it been around? Who knows. But at some point, the summertime bullying calcified into mythology and now Eli is the recipient.

And critically, he’s contagious. The boys tell Ben that if Eli ever touches him, he must shower immediately to avoid contracting this physical/social disease.

While we can tell that Ben is more sensitive (outwardly, at least) than the other boys, he still participates in this dynamic because that’s how cliques work. You don’t get protection for free. You typically pay with someone else’s dignity. The film makes this point without ever becoming preachy, which I appreciate.

Despite the constant scrutiny, Eli is unapologetically himself. He dances with abandon with his cardboard cut-out cartoon girlfriend, performs magic tricks for Ben, sits in the sauna for questionably long stretches to self-regulate, and sleeps in the locker room to avoid being bullied at night. He appears unbothered, and this bothers Ben to his core.

But Eli is not unbothered. He just doesn’t cave to the group’s disgust. Eli hides from his abusers at night, but he never tries to change himself to earn their approval. It’s clear that he’s in pain, but he’s making no moves to assimilate.

The film allows empath Ben to be complicit and downright cowardly at times. When he begins privately connecting with Eli and questioning Jake’s behavior, the group turns on him, to his absolute horror. And all of that goodwill he cultivated evaporates overnight.

The boys begin hazing him while he sleeps, and you can’t help but wonder where the hell the adults running this camp are. But that’s where the 2003-ness of it all comes in handy, because it’s the tail end of the latchkey kid era and no one’s checking in at night.

During the day, the adults are technically present, but their presence changes nothing. Joel Edgerton (who has impeccable taste in roles) plays the water polo coach, nicknamed “Daddy Wags.” (No idea how he earned that name, and I refuse to ponder it.) He’s an aloof man who offers pep talks that sound comforting in the moment but are ultimately useless.

He scolds Jake privately and prioritizes order over care, but he’s not a monster. Daddy Wags is an emotionally unavailable, conflict-averse water polo coach who confesses to Ben that he was bullied for being overweight as a kid. That revelation is meant to be comforting until he rambles on about how things maybe kinda get better in your forties, and you should probably just suck it up. The top note: You’re on your own. Deal with it.

In a move that calls to mind Julia Ducournau’s and Black Swan, the film frames acts of self-harm and grooming as body horror, from popping pimples to picking at skin on the fingers to self-soothe. Anxiety becomes physical as inflamed rashes begin to appear all over Ben and Eli. The body is keeping the hell out of the score, and it ain’t subtle about it. Like Nina’s unraveling in Black Swan, Ben’s transformation is a stressful shedding of all of his illusions about belonging and goodness.

The film builds toward a final confrontation that forces Ben to confront the truth, and you walk away thinking about the cost of belonging and how it can put you in situations that compromise your personal values.

The Plague doesn’t offer easy villains, even though Jake is largely insufferable throughout. But what it does offer is a stark look at how thin the line is between membership and exile.

Leave a comment