Memories are tricky because they are reconstructions that can be influenced and reshaped by our emotional state, belief systems, ego, environment and many other factors. It’s why 10 people can witness a single event and recall 10 distinct versions of it.

Memories are unreliable, but our reliance on them shapes our lives.

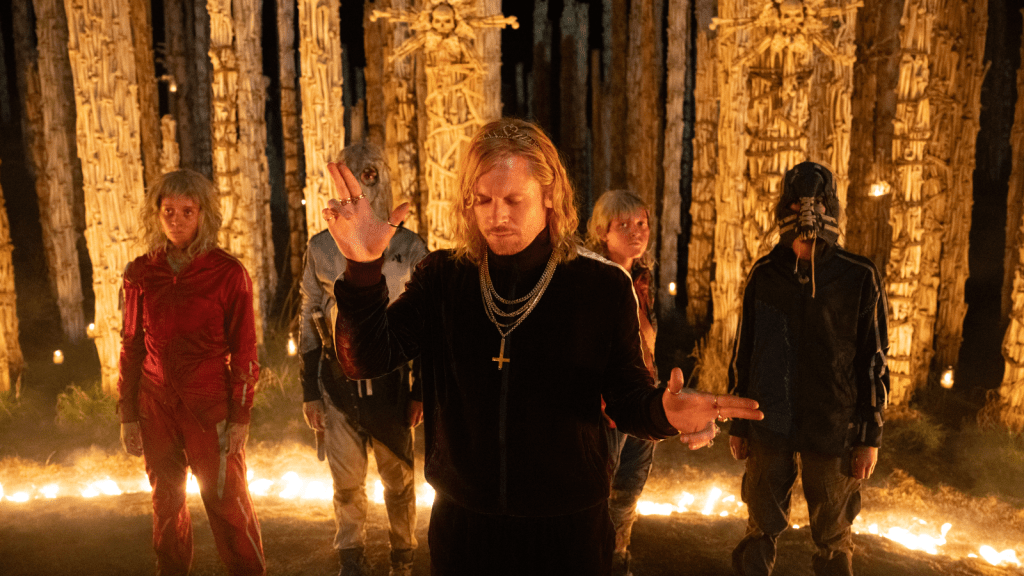

In Nia DaCosta’s 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, memory becomes another form of infection in a postapocalyptic Europe reeling with a rage virus. Fresh off Sinners, Jack O’Connell stars as the film’s big bad, Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal, a violent man whose childhood trauma and faulty memories drive him to recruit other wounded souls to do his bidding.

I won’t spoil the ending or anything too pivotal, but you need to understand what Jimmy thinks he saw back when he was 8, because the rest of his life is just him trying to resync with a past that’s long gone and not exactly grounded in reality.

In 28 Years Later, we meet Jimmy as a boy. He and a few other children are seated in the family room of a home watching Teletubbies on TV. But this is no normal enrichment time. The age of rage has begun, and we hear zombies screeching just outside as the adults in other rooms scramble to defend themselves and the children.

As Tinkie Winkie and pals bounce around on that grassy knoll on the TV, one young girl sobs uncontrollably. A few others dissociate, and young Jimmy lingers by the door, trying to see what’s happening. Inevitably, everything goes to shit, but we stay with Jimmy as he flees to a nearby church where his pastor father is.

You might expect Jimmy’s pops to be praying or frantic, but he’s in full calm mode. As a horde of infected claw at the church windows and doors, desperate to get inside, he tells his son this is destiny. He presses a cross necklace into Jimmy’s hand as his sobbing son looks on in horror.

When the doors finally give way, his father drops to his knees, arms open and ready to receive. The infected swarm him like devoted followers before tearing him apart and welcoming him into their cursed hive. And a confused young Jimmy watches from a vented crawlspace, and we see his understanding of reality collapsing as he watches his father get consumed.

Twenty-eight years later, in the Bone Temple, Jimmy has transformed into Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal, the leader of a mini-cult of ultraviolent teens called The Fingers. In colorful Teletubbie-colored tracksuits and choppy blond wigs that resemble Jimmy’s luscious locks, these kids can flip and tumble like Power Rangers and murder and maim like Leatherface and Buffalo Bill combined, and they’re all named Jimmy—Jimmy Ink, Jimmy Fox, Jimmy Shite, Jimmy Jimmy, Jimmy Snake and Jimmima.

(The film’s cult leader is inspired by the late UK comedian and TV host Jimmy Savile, whose predatory crimes wouldn’t be exposed until long after the virus had already taken hold. Sir Jimmy only knows him as a charming radio DJ and media personality because he lost access to the media at age 8.)

Jimmy Crystal is a sadistic man who follows the command of the voice in his head, and that voice belongs to Old Nick. Jimmy believes Old Nick is both satan and his father because when he watched his dad break from reality decades ago, he told himself this story to process this horrifying trauma.

This is where the film pushes back against the concept of good vs. evil and instead takes a humanist approach. If Old Nick only exists in Jimmy’s head, is he pure evil? Or is he a traumatized person with severe mental health issues who’s trying to find a way back to his late father, who he truly believes is the devil after what he witnessed as a kid, and the only way to do so is to commit one heinous act after another. Is there a way to reform this type of person, or must he be condemned as beyond saving?

Digging into the concept of “good,” this installment of the franchise shows us that the virus affects how the infected see the world. They view others who are virus-free as infected attackers. Knowing that they aren’t these soulless vessels of murderous rage changes the game and restores some of their humanity.

In a world where there is no structure or law and order, and perception can be weaponized, how is good defined? Can you retain that label as you shoot arrows through the hearts and heads of throngs of infected people when you leave your protected island to go hunt in their territory?

Circling back to the unreliability of memories, Dr. Kelson— played by Ralph Fiennes, who gives one of my favorite performances of his in recent years— is a chaotically good contrast to “evil” Jimmy. He’s an unconventional doctor who understands and embraces the balance of the human condition. We see this through his stoic practice of memento mori (remember that you will die) and memento amoris (remember love).

When Sir Lord Jimmy enters the Bone Temple unannounced, he and Kelson have a tête-à-tête that shows us their differences and underlines the memory conflict. Jimmy was 8 when the rage virus emerged, but Dr. Kelson was much older. Jimmy recalls watching “tele-tummies,” a faulty misremembering, but a core memory as strong as that of his father embodying Satan.

The rage virus may destroy the body, but a warped memory can destroy the soul.

Kelson, on the other hand, has a stronger and more neutral memory of the beforetimes. He recalls a world with a sense of certainty and order and foundations that seemed unshakable. (Sigh, same here, doc.)

This is a conflict that every generation reckons with. We all have our own version of the beforetimes. I personally romanticize growing up in the ’90s on the reg, but there were plenty of terrible events that I glaze over to hold onto this idea of a world with less turmoil. Was it less tumultuous because I was young and dumb without financial responsibilities, in a time when physical media reigned supreme, and there were no smartphones to record all of the ways I socially failed? Yes. A big ol’ emphatic yes.

And that’s what Bone Temple understands so well: The past is never quite as we remember it, and memory can be a dangerous refuge. Most of the time, it’s a story we keep rewriting just to survive the present.

If you can stomach zombie films, I recommend watching 28 Days Later and 28 Years Later on Netflix (28 Weeks Later is non-canon) before heading to the theater to catch Bone Temple. It’s a timely must-watch that explores survival as much as remembrance, and suggests there may still be another way out of the madness.

Leave a comment