Finding funding for independent films has always been challenging, especially for emerging filmmakers tackling sensitive topics. But after attending over a dozen Q&As at various AMCs, Landmarks and Laemmles across Los Angeles over the past year and listening to directors and actors speak candidly about the hellacious development process, I realized that it really is a miracle that any movie gets made, including the transgressive indies that I adore so much.

I didn’t realize how personal it all would become for me until I heard Caleb Landry Jones, one of my favorite actors, admit that his upcoming passion project could potentially not see the light of day because there’s not much appetite for socially conscious material right now. (If only more members of the donor class were investing in the arts instead of bunkers and data centers.)

Before I began attending Q&As for sport (and filming them for YouTube), I had my very own a-ha indies-are-in-danger moment. It happened during a hours-long wait for the Mobile Criterion Closet. A friend and I were discussing our potential closet picks with someone in “the industry,” and Céline Sciamma’s Petit Maman came up. You may not recognize the name immediately, but Sciamma is the acclaimed director of Portrait of a Lady on Fire, which, for my money, is one of the greatest films of the 2010s.

Her follow-up to Portrait, Petit Maman, is about a young girl grieving her grandmother, who forms an unexpected friendship that bends time and deepens her connection to her mother. That film pulled my heartstrings straight out of my chest. It also made only around $2 million bucks worldwide against a reported budget of $3 million.

Sciamma’s films, which speak so intimately to womanhood and girlhood, aren’t gonna top the box office, and that should be just fine because there are others designed to do that. Her work is pivotal to cinema as a whole.

So when the “insider” told us that Sciamma had become disillusioned with the business and was taking a step back, we were just straight-up dejected. She’s exactly the kind of filmmaker you wish could make whatever they wanted, without limits. (I have a long list of those, including Boots Riley, Nia DaCosta, Julia Ducournau, Peter Brunner, Bong Joon-ho, Barry Jenkins, Park Chan-wook, Ira Sachs and like 30 others who I’d personally fund if I won the Powerball.)

Show business is a business, and business prioritizes financial viability above all else. What would Sciamma have to do to get her next film funded? What compromises were asked of her?

The push to make money is nothing new, but there was a sweet little pocket of time in the ‘90s/00s when indie film was booming. Nowadays, target demographics, high-concept loglines, IMDb power rankings and social media follower counts are messing everything up. Now it’s all:

To make matters even worse, box office figures have become a weekly social media blood sport, with armchair critics treating art like a scoreboard. And thanks to the pandemic, the strikes, the economy and streaming services assembling like Transformers to undercut the theatrical experience, the arthouse movies that I trek from the Westside to Burbank to see are becoming fewer and farther between.

Unfortunately, Sciamma is no outlier. Harris Dickinson is about to play John Lennon, starred in the acclaimed Triangle of Sadness (and one of those Kingsmanaction movies), and he still couldn’t get Urchin, his film about a young man experiencing addiction and homelessness, financed without a fight.

“It’s not necessarily the kind of film people wanted to throw their money at,” Dickinson told the LA Times. “And if I’m being honest, there was probably a general rhetoric of ‘You’re just some actor who wants to have a go.’ I get that, but it’s been a long ambition and [there was] a deep care and a lot of love and time. It was probably there before my acting career was there.”

It’s a film made with care and intention, one that Dickinson spent years developing to ensure he was approaching everything responsibly. The final product is moving, sometimes funny, sometimes bleak and a definite conversation starter.

Fiction, whether in cinema or book form, helps develop empathy. It opens your eyes to experiences outside of your little bubble. The resistance to financing narratives that force us to confront what we’d rather leave unseen saddens me. Because I want a glimpse into the fictional lives of people of all backgrounds. I’m greedy for it.

There’s also the question that haunts every film about homelessness before a single dollar is invested. What does it mean to put poverty on screen at all?

Nomadland famously cast real people playing versions of themselves, and in that sense, it nods toward authenticity. But their experiences take a backseat to Fern, played by Frances McDormand, and there’s a tone that some might say softens the reality of what it’s depicting.

It’s a balancing act for sure. You want to spotlight a community and challenge viewers to face the unknown or destroy the stereotype they harbor, but nuance is necessary. You can find joy while being housing-unstable (I’ve been there as a kid). However, there are terribly dark situations to contend with as well.

So many American films about deep poverty lean toward feel-good mushiness or the bootstraps narrative that some of the upperclass have been conditioned to love. In these, homelessness becomes a temporary obstacle, rather than a systemic and often debilitating reality.

And somewhere in the middle of that Disney-fied homeless experience to trauma porn spectrum is social realism, a genre I wish Hollywood would embrace. Films that give a voice to the voiceless.

Imagine if there were more films like Beasts of the Southern Wild? That breakout hit earned more than $21 million globally and was made for under $2 million. Tell me again that the right social impact story can’t be universally beloved and successful.

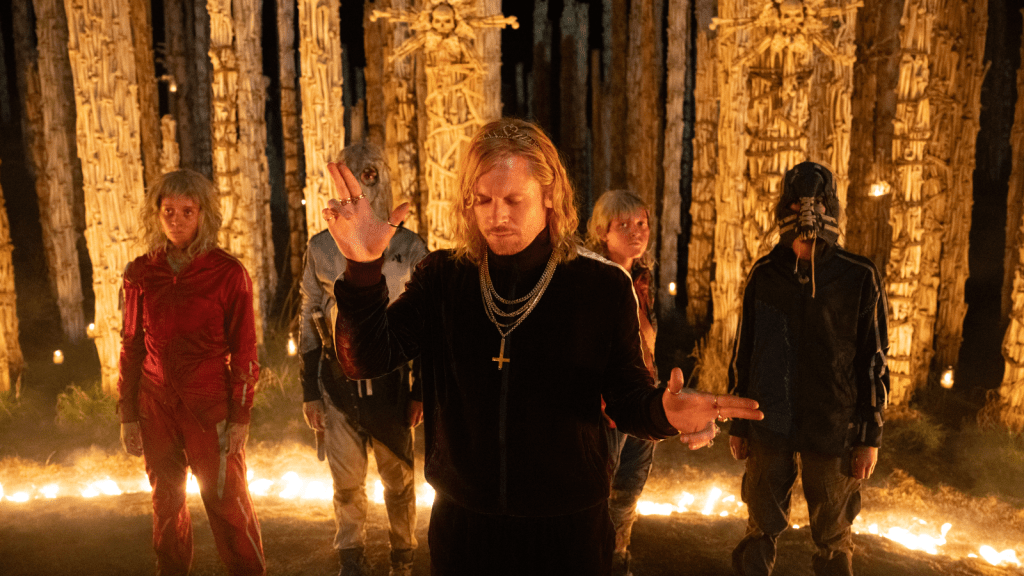

Now let me land this plane by circling back to the endangered project that I desperately want to see the light of day: Caleb Landry Jones’ upcoming indie drama Down the Arm of God.

The film centers on a young pastor in Texas whose attempt to aid people who are unhoused during a brutal winter is met with hostility from his own church. Built from real-life stories, it’s a drama about systemic failure and confronting bias.

It couldn’t be more timely because the line between this piece of fiction and reality is blurry as all hell. This month, as a massive winter storm has swept across nearly half the country, at least 10 unhoused people have died in New York City due to freezing temperatures.

On top of that, we are grappling with religion getting weaponized in real time as one policy after another takes aim at our most vulnerable populations.

Peter Brunner, the film’s director and co-writer, told Variety: “It’s been the most beautiful experience, thanks to reteaming with Caleb, and also the most complicated movie I’ve ever made — not because of working with our unhoused friends, but due to the sheer number of rules and requirements imposed on them. These restrictions expose just how many additional obstacles they face simply for being on the streets. They are not treated the same.”

A few days ago, I attended a Q&A with Caleb and Christoph Waltz, hoping for an announcement of a release date, something I could lock into my calendar. And boy, oh, boy, was I not prepared for the update I did get.

“It’s a film that I believe very much in,” he said. “With people who very much need a voice. I think that kind of work is very important. It’s a social impact film, I guess you could say, and those films are very hard to make, and nobody wants them right now. It’s frustrating.”

Nobody wants them right now carries such a nasty implication. That the people with money don’t believe there’s an audience for a film like this. Those stories built around the unhoused community—who’ve been dehumanized in the media and beyond because we place moral value on housing and employment—are off trend. It’s the kind of thing that makes you want to flip a table.

I haven’t seen the film yet, and I only know what’s been shared publicly. But based on the five years Caleb and his team spent immersed with unhoused communities, and his previous partnership with Brunner on To the Night, I can’t help but imagine something nuanced and engrossing.

The rise of Gen-AI adds a whole other layer of crisis as studios turn to it to replace human labor and maximize profits. But the backlash to projects built entirely around artificial performance shows that people, thankfully, aren’t ready to embrace movies starring AI-generated actors and settings. Yet, at least.

So when Caleb says nobody wants these films right now, it feels bigger than one project in limbo. I hear an industry shrinking itself down to glomb onto whatever feels easiest to monetize. Fewer and fewer big swings and more sure things (if there is such a thing anymore).

I rebuke that. I rebuke it so hard.

Audiences will show up for these types of stories when they are engaging and handled with care. At the end of the day, marketing plays a huge role. We can’t see what we don’t know exists.

An imaginative and thoughtful campaign can help an indie stand out and get seen. I recently found out there are organizations built for exactly this.

Picture Motion builds full-scale advocacy campaigns around films like these, linking filmmakers with activists, nonprofits, educators and communities, then mobilizing an audience through partnerships and outreach.

Over the past decade, they’ve worked on hundreds of projects, including American Fiction and Bob Trevino Likes It, so I’m hoping they find their way over to someone on the Down the Arm of God team. Seems like an ideal partnership if ever there was one.

Homelessness in Texas is a growing issue. In 2023, more than 27,000 people were counted as unhoused on a single night. Over 61,000 unique individuals accessed homelessness services during that same year. The numbers continue to rise as housing remains unaffordable in the Lone Star State and the country as a whole.

Homelessness is a crisis that affects millions of people across the globe, around 700,000 people in the US, and it’s solvable. It’s something that could be eradicated in our lifetime. Films like Down the Arm of God can put faces and stories to those numbers. They just need a chance to be seen and find their audience.

Leave a comment