After performing with his amateur a cappella group at a dive bar, a shy young man catches the attention of a handsome, stoic biker while ordering crisps (chips). The Christmastime encounter sends him on a journey of self-discovery that pushes his limits and forces him to learn to set his own boundaries.

It’s a pretty standard coming-of-age rom-com framework, but set inside a queer subculture that has existed on the periphery since at least the mid-twentieth century. That perspective is what sets Pillion apart from heteronormative holiday romances like The Holiday and Love, Actually.

That positioning makes the film feel especially unique for a Valentine’s Day release. While Emerald Fennell courts audiences with the windswept melodrama and corseted spectacle of her divisive Wuthering Heights adaptation and Dracula: A Love Tale leans into treacly monster romance territory, A24’s Pillion stands out with its leather-clad hookups and negotiated intimacy embedded in a rom-com structure that is all too familiar for those who enjoy a good ol’ yearn-and-chuckle fest.

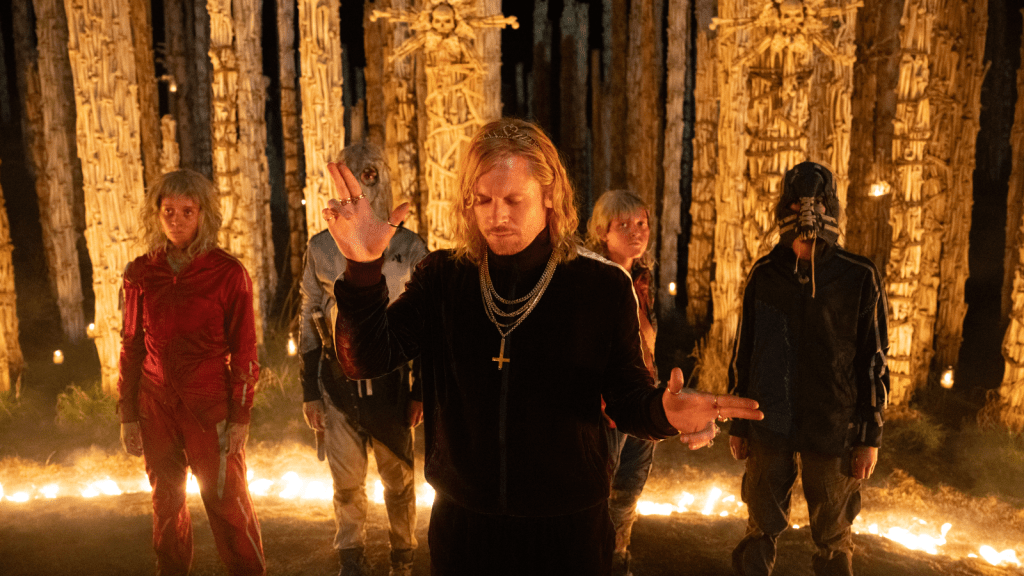

Written and directed by Harry Lighton, Pillion is based on Adam Mars Jones’ novella, Box Hill: A Story of Low Self-Esteem, and follows Colin (Harry Melling), a timid parking warden whose emotional outlet is a small a capapella group. His life runs on politeness and routine, until he meets Ray, played by Alexander Skarsgård, a super-controlled biker dom whose kink is structure, specifically high protocol, which means he is extra strict.

For those of you, like myself, who’ve never heard of the word “pillion” before, know that it’s a razor-sharp title that nails the film’s themes. A pillion is a motorcycle’s passenger seat, sometimes called the “bitch seat,” a direct reflection of the power dynamic between Ray, the dom driver, and his sub, Colin, who rides “bitch.” It’s lowkey shocking to me that they didn’t call the film something generic like “The Biker,” as a person who loathes generic titles because they suggest the audience is too dumb to buy into a movie that doesn’t blandly spell itself out in the title.

Last week, I attended a screening Q&A with Lighton, Melling and Skarsgård, moderated by François Arnaud of Heated Rivalry. Lighton spoke about the five-year development process that began with a completely different idea about sumo wrestling. Then the pandemic hits, that project stalls, and the head of the BBC sends him Jones’s novella with a note saying, “I think you’ll like it.” The tone of the book immediately hooks him in, particularly the way it pivots between comedy, sincerity and shock. He said that translating Colin’s interior voice into a visual language was the core challenge, and the adaptation grew from there.

For his directorial debut, Lighton took massive experimental swings along the way. At one point, the story was set in ancient Rome inside a gladiator school, but that didn’t quite work. (I’d like to see that version BTW). Another iteration took place on a cruise ship, but it costs an insane amount to film on one. Eventually, he returned to the queer biker world of the novella, and things just snapped into focus.

Skarsgård said he was drawn to how funny and awkward the script felt and how it refused to buff the dynamic into something slicker, which is a hat trick unto itself.

The film asks a deceptively simple question: What happens when you plug a dom-sub relationship into the structure of a mainstream rom-com? The answer is something pretty brilliant.

You know the typically goofy/tense “dinner with the parents” rom-com trope? We’ve seen it a million times, right? Well, in Pillion, it becomes ideological warfare. Lighton says, “If you’re bringing your partner around who’s like a dom who doesn’t tell you his last name, it’s gonna chafe a little bit. So there was like an interesting effort we made to test it against the rom-com and see where it failed or surpassed it.’” Colin’s mom, who is terminally ill, questions their relationship, and Ray calls her all the way out so bluntly that our entire audience gasped.

Unlike Fifty Shades of Grey or The Secretary, the rules of BDSM are not spelled out for viewers or Colin. Ray is a man of few words, who speaks in side glances and carefully written, instructive notes. He doesn’t ask Colin for permission and Colin doesn’t push for details. He mildly bristles, then obeys Ray’s commands, making adjustments along the way, until he finds his own limits and sets a boundary for Ray.

I’m no BDSM scholar, but I imagine that this representation of the community could be divisive because consent is murky AF, and the lack of communication feels like it borders on abuse, especially because Colin is so impressionable and meek. You, as a viewer, build up this defensiveness on his behalf. But the whole point is that our first relationships are rarely perfect or built on a foundation of respect and good communication. Things are bumpy, and you learn about yourself and what you like—and don’t—and hopefully grow from the experience, making adjustments for yourself and your next partner.

In this case, Ray is avoidant-dismissive, which means he values independence to the point of emotional distance. Dealing with this attachment style is tricky even for people with experience and an unshakable sense of self. This is a coming-of-age film at its core, and eventually, Colin, well, comes of age and figures out how to assert himself and prioritize his own needs.

Despite the challenges in their situationship, the film is not all tension and gloom. It laughs at itself throughout. Ray reads Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle: Book One before bedtime, a heavy read that maps the structures that govern this Norwegian dude’s life. Real ones in the audience guffawed at this bit.

Later in the film, the pair spend a day off together, which was so sweet and charming that your inner rom-com fan almost expects to hear Katrina and the Waves’ “Walking on Sunshine.” Overall, you can sense the care that was taken by both the actors and Lighton throughout the movie, which does not end in doom.

Quick aside: After the screening, I ambled over to Skarsgård with a copy of my War on Everyone Blu-ray (the British anti-buddy-cop flick co-starring Caleb Landry Jones and Tessa Thompson that received a petite US theatrical release). I asked him to sign it, and he did, then I asked for a photo, and he obliged. So there is now photographic evidence of me standing next to one of my favorite actors, the six-foot-something Swedish man who’s starred in my beloved The Northman and True Blood. Bliss!

Now to wrap this up. I need all of the yearners to show up and show out for theatrical rom-com releases, and not just for the glossy star pairings like Sydney Sweeney and Glen Powell in Anyone but You. High-concept swings, like the underrated Lisa Frankenstein, fail to find much love at the box office, signaling to gatekeepers that there’s no market for unconventional love stories. I believe there is. Pillion is one, a really good one too, and I hope it does well in theaters. We rarely get films that interrogate desire within a specific queer subculture and still commit to genre pleasure. Jeff Nichols’ The Bikeriders flirted with that, though its queerness was mostly subtext. I say mostly, because Tom Hardy was like millimeters away from planting a kiss on Austin Butler as they spoke in whispers during that one gorgeously lit scene.

So audiences may be flocking to the Yorkshire moors for a kinky reimagining of Brontë’s novel over the next couple of weekends. But if you’re in the mood for something layered and carnal and don’t mind a little prosthetic peen, Pillion is the better ride. The genre might still be in the driver’s seat, but the film reminds us that there’s power (and pleasure) in choosing when to ride bitch.

Leave a comment